What Animal Is Considered The Closest Ancestor To Dinosaurs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/China-Dinosaurs-Xu-Xing-Psittacosaurus-631.jpg)

In a pine forest in rural northeastern China, a rugged shale slope is packed with the remains of extinct creatures from 125 meg years agone, when this part of Liaoning province was covered with freshwater lakes. Volcanic eruptions regularly convulsed the area at the time, entombing untold millions of reptiles, fish, snails and insects in ash. I pace gingerly among the myriad fossils, pick up a shale slab non much larger than my hand and smack its edge with a rock hammer. A seam splits a russet-colored fish in one-half, producing mirror impressions of frail fins and bones as sparse as human hairs.

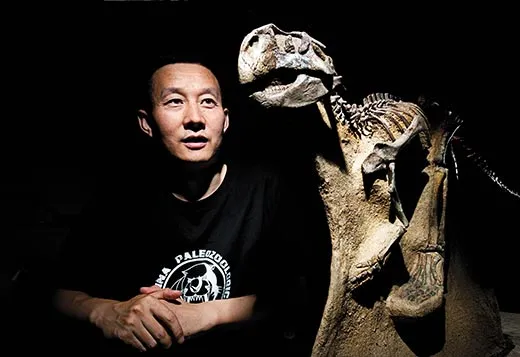

One of China's star paleontologists, Zhou Zhonghe, smiles. "Amazing place, isn't it?" he says.

It was in 1995 that Zhou and colleagues announced the discovery of a fossil from this prehistoric disaster zone that heralded a new historic period of paleontology. The fossil was a primitive bird the size of a crow that may accept been asphyxiated by volcanic fumes as it wheeled to a higher place the lakes all those millions of years agone. They named the new species Confuciusornis, later on the Chinese philosopher.

Until then, simply a scattering of prehistoric bird fossils had been unearthed anywhere in the world. That's partly because birds, then equally now, were far less common than fish and invertebrates, and partly because birds more readily evaded mudslides, tar pits, volcanic eruptions and other geological phenomena that captured animals and preserved traces of them for the ages. Scientists accept located only ten intact fossilized skeletons of the earliest known bird, Archaeopteryx, which lived at the cease of the Jurassic menstruum, almost 145 meg years ago.

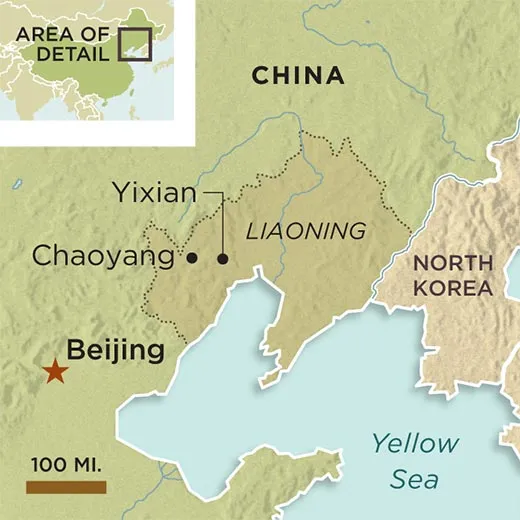

Zhou, who works at the Plant of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, believed that the extraordinary bone beds in Liaoning might fill in some of the many blanks in the fossil record of the earliest birds. He couldn't have been more prophetic. In the by 15 years, thousands of exquisitely preserved fossil birds have emerged from the ancient lakebed, called the Yixian Formation. The region has also yielded stunning dinosaur specimens, the likes of which had never been seen before. As a result, China has been the central to solving i of the biggest questions in dinosaur science in the past 150 years: the existent human relationship between birds and dinosaurs.

The idea that birds—the almost diverse group of land vertebrates, with nearly 10,000 living species—descended directly from dinosaurs isn't new. It was raised by the English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley in his 1870 treatise, Further Evidence of the Affinity between the Dinosaurian Reptiles and Birds. Huxley, a renowned anatomist perhaps best remembered for his ardent defense of Charles Darwin'southward theory of evolution, saw piddling difference between the bone structure of Compsognathus, a dinosaur no bigger than a turkey, and Archaeopteryx, which was discovered in Germany and described in 1861. When Huxley looked at ostriches and other modernistic birds, he saw smallish dinosaurs. If a baby chicken's leg bones were enlarged and fossilized, he noted, "in that location would be nothing in their characters to prevent us from referring them to the Dinosauria."

Still, over the decades researchers who doubted the dinosaur-bird link also fabricated good anatomical arguments. They said dinosaurs lack a number of features that are distinctly avian, including wishbones, or fused clavicles; bones riddled with air pockets; flexible wrist joints; and iii-toed anxiety. Moreover, the posited link seemed reverse to what everyone idea they knew: that birds are small, intelligent, speedy, warmblooded sprites, whereas dinosaurs—from the Greek for "fearfully great lizard"—were coldblooded, dull, plodding, reptile-like creatures.

In the late 1960s, a fossilized dinosaur skeleton from Montana began to undermine that assumption. Deinonychus, or "terrible claw" after the sickle-shaped talon on each hind foot, stood about eleven anxiety from head to tail and was a lithe predator. Moreover, its bone construction was similar to that of Archaeopteryx. Presently scientists were gathering other intriguing physical evidence, finding that fused clavicles were mutual in dinosaurs afterward all. Deinonychus and Velociraptor bones had air pockets and flexible wrist joints. Dinosaur traits were looking more birdlike all the fourth dimension. "All those things were yanked out of the definition of beingness a bird," says paleontologist Matthew Carrano of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Just there was one important characteristic that had non been found in dinosaurs, and few experts would experience entirely comfortable asserting that chickadees and triceratops were kin until they had bear witness for this missing anatomical link: feathers.

A poor Chinese farmer, Li Yingfang, made one of the greatest fossil finds of all fourth dimension, in August 1996 in Sihetun hamlet, an hour's drive from the site where I'd prospected for fossil fish. "I was digging holes for planting trees," recalls Li, who now has a full-time job at a dinosaur museum congenital at that very site. From a hole he unearthed a ii-foot-long shale slab. An experienced fossil hunter, Li split the slab and beheld a creature dissimilar any he had seen. The skeleton had a birdlike skull, a long tail and impressions of what appeared to be feather-like structures.

Because of the feathers, Ji Qiang, and then the director of the National Geological Museum, which bought ane of Li's slabs, assumed it was a new species of primitive bird. Just other Chinese paleontologists were convinced it was a dinosaur.

On a visit to Beijing that October, Philip Currie, a paleontologist at present at the Academy of Alberta, saw the specimen and realized information technology would turn paleontology on its head. The next month, Currie, a longtime China paw, showed a photograph of it to colleagues at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. The picture stole the show. "Information technology was such an amazing fossil," recalls paleontologist Hans-Dieter Sues of the National Museum of Natural History. "Sensational." Western paleontologists soon made a pilgrimage to Beijing to see the fossil. "They came back dazed," Sues says.

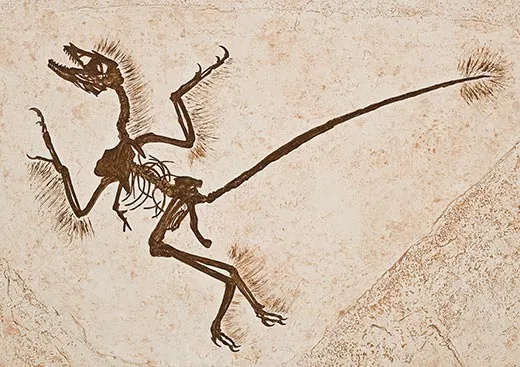

Despite the feathers, the skeleton left no doubtfulness that the new species, named Sinosauropteryx, meaning "Chinese lizard wing," was a dinosaur. It lived around 125 million years ago, based on the dating of radioactive elements in the sediments that encased the fossil. Its integumentary filaments—long, thin structures protruding from its scaly skin—convinced virtually paleontologists that the animal was the first feathered dinosaur ever unearthed. A dozen dinosaurs with filaments or feathers take since been discovered at that site.

Past analyzing specimens from China, paleontologists have filled in gaps in the fossil record and traced the evolutionary relationships among various dinosaurs. The fossils finally have confirmed, to all but a few skeptics, that birds descended from dinosaurs and are the living representatives of a dinosaur lineage called the Maniraptorans.

Most dinosaurs were not part of the lineage that gave rise to birds; they occupied other branches of the dinosaur family unit tree. Sinosauropteryx, in fact, was what paleontologists call a non-avian dinosaur, fifty-fifty though information technology had feathers. This insight has prompted paleontologists to revise their view of other non-avian dinosaurs, such as the notorious meat eater Velociraptor and even some members of the tyrannosaur grouping. They, too, were probably adorned with feathers.

The abundance of feathered fossils has allowed paleontologists to examine a fundamental question: Why did feathers evolve? Today, information technology's clear that feathers perform many functions: they assist birds retain body heat, repel water and attract a mate. And of course they help flying—simply not always, as ostriches and penguins, which have feathers but do not fly, demonstrate. Many feathered dinosaurs did not have wings or were too heavy, relative to the length of their feathered limbs, to fly.

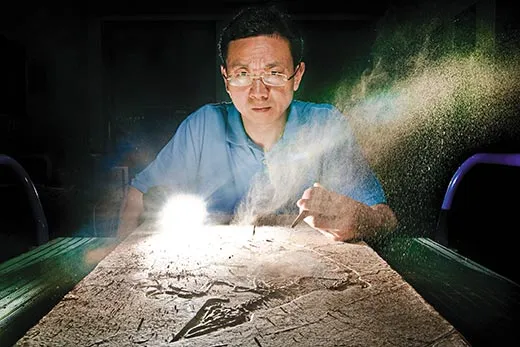

Deciphering how feathers morphed over the ages from spindly fibers to delicate instruments of flight would shed light on the transition of dinosaurs to birds, and how natural option forged this complex trait. Few scientists know aboriginal feathers more than intimately than IVPP'south Xu Xing. He has discovered forty dinosaur species—more than any other living scientist—from all over Cathay. His office at IVPP, across the street from the Beijing Zoo, is chaotic with fossils and casts.

Xu envisions feather evolution as an incremental process. Feathers in their about primitive form were unmarried filaments, resembling quills, that jutted from reptilian peel. These elementary structures go manner back; even pterodactyls had filaments of sorts. Xu suggests that feather evolution may have gotten started in a common ancestor of pterodactyls and dinosaurs—almost 240 million years ago, or some 95 million years before Archaeopteryx.

After the emergence of single filaments came multiple filaments joined at the base. Side by side to announced in the fossil record were paired barbs shooting off a cardinal shaft. Eventually, dense rows of interlocking barbs formed a flat surface: the basic pattern of the then-chosen pennaceous feathers of modern birds. All these feather types have been found in fossil impressions of theropods, the dinosaur suborder that includes Tyrannosaurus rex also equally birds and other Maniraptorans.

Filaments are establish elsewhere in the dinosaur family unit tree as well, in species far removed from theropods, such equally Psittacosaurus, a parrot-faced herbivore that arose effectually 130 million years ago. It had sparse unmarried filaments along its tail. It's not clear why filaments appear in some dinosaur lineages but not in others. "One possibility is that feather-like structures evolved very early on in dinosaur history," says Xu, and some groups maintained the structures, while other groups lost them. "But finally in Maniraptorans, feathers stabilized and evolved into modern feathers," he says. Or filaments may take evolved independently at different times. As Sues points out, "It seems that, genetically, it'southward not a great fob to make a scale into a filament."

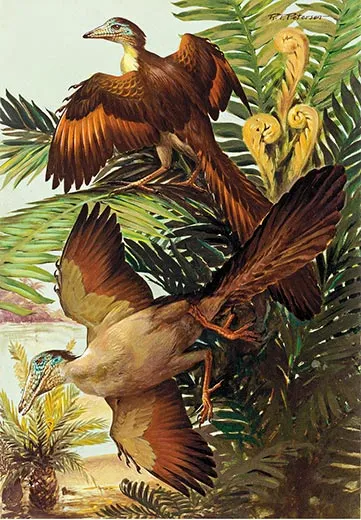

Originally, single filaments may well have been for brandish, the dinosaur equivalent of a peacock'due south irised plumage. Vivid prove for that theory appeared when scientists unveiled the truthful colors of 125-million-year-old feathers. Bird feathers and reptile scales incorporate melanosomes—tiny sacs holding varieties of the pigment melanin. Many paleontologists suspected that dinosaur feathers also contained melanosomes. In Mike Benton's laboratory at the Academy of Bristol, IVPP'southward Zhang Fucheng spent more than a year searching for melanosomes in photographs of bird and dinosaur fossils taken with an electron microscope. Zhang'south diligence paid off in 2009 when he pinpointed melanosomes in Confuciusornis that contained eumelanin, which gives feathers a gray or black tinge, and pheomelanin, which gives them a chestnut to reddish-dark-brown color. The creature's feathers had patches of white, black and orangish-brownish coloring.

Sinosauropteryx was even more than stunning. Zhang establish that the filaments running down its back and tail must take made the dinosaur look similar an orange-and-white-striped hairdresser pole. Such a vibrant pattern suggests that "feathers first arose as agents for colour display," Benton says.

Early feathers could have served other purposes. Hollow filaments may have dissipated oestrus, much as the frills of some mod lizards exercise today. Other paleontologists speculate feathers offset evolved to retain oestrus. A telling instance comes from fossils of Oviraptor—a theropod unearthed in Mongolia that lived around 75 million years ago—squatting over egg-filled nests. Oviraptors tucked their legs into the center of the clutch and hugged the periphery with their long forelimbs—a posture bearing an uncanny resemblance to heart-searching birds keeping their eggs warm. Dinosaurs related to Oviraptor were covered with pennaceous feathers, suggesting that Oviraptor was as well. "Sitting on a nest like that only made sense if it had feathers" to gently insulate its immature, says Sues.

Feathers did, of form, eventually get an instrument of flight. Some paleontologists envision a scenario in which dinosaurs used feathers to help them occupy trees for the showtime time. "Because dinosaurs had hinged ankles, they could non rotate their anxiety and they couldn't climb well. Maybe feathers helped them scramble up tree trunks," Carrano says. Baby birds of primarily basis-dwelling species like turkeys apply their wings in this way. Feathers may take go increasingly aerodynamic over millions of years, eventually assuasive dinosaurs to glide from tree to tree. Individuals able to perform such a feat might take been able to reach new nutrient sources or better escape predators—and pass the trait on to subsequent generations.

I of the most beguiling specimens to sally from Liaoning'southward shale beds is Microraptor, which Xu discovered in 2003. The bantamweight animate being was a foot or two long and tipped the scales at a mere two pounds. Microraptor, from the Dromaeosaur family unit, was not an antecedent of birds, just information technology was too unlike any previously discovered feathered dinosaur. Xu calls it a "iv-winged" dinosaur considering it had long, pennaceous feathers on its arms and legs. Because of its fused breastbone and asymmetrical feathers, says Xu, Microraptor surely could glide from tree to tree, and it may even accept been better at flying under its own ability than Archaeopteryx was.

Final year, Xu discovered another species of four-winged dinosaur, also at Liaoning. Besides showing that four-winged flying was not a fluke, the new species, Anchiornis huxleyi, named in award of Thomas Henry Huxley, is the earliest known feathered dinosaur. It came from Jurassic lakebed deposits 155 1000000 to 160 million years old. The observe eliminated the final objection to the evolutionary link betwixt birds and dinosaurs. For years, skeptics had raised the and then-chosen temporal paradox: there were no feathered dinosaurs older than Archaeopteryx, so birds could non have arisen from dinosaurs. Now that argument was blown away: Anchiornis is millions of years older than Archaeopteryx.

Four-winged dinosaurs were ultimately a dead branch on the tree of life; they disappear from the fossil record around 80 million years ago. Their demise left only one dinosaur lineage capable of flight: birds.

Just when did dinosaurs evolve into birds? Difficult to say. "Deep in evolutionary history, information technology is extremely hard to describe the line between birds and dinosaurs," says Xu. Aside from minor differences in the shape of neck vertebrae and the relative length of the arms, early birds and their Maniraptoran kin, such every bit Velociraptor, await very much alike.

"If Archaeopteryx were discovered today, I don't call back you would call information technology a bird. You lot would call it a feathered dinosaur," says Carrano. It's yet called the first bird, but more for historic reasons than considering information technology is the oldest or best embodiment of birdlike traits.

On the other hand, Confuciusornis, which possessed the first neb and primeval pygostyle, or fused tail vertebrae that supported feathers, truly looks like a bird. "It passes the sniff test," Carrano says.

Since the last of the not-avian dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago during the mass extinction that closed the pall on the Cretaceous menses, birds take evolved other characteristics that prepare them apart from dinosaurs. Modern birds take higher metabolisms than fifty-fifty the nearly agile Velociraptor ever had. Teeth disappeared at some betoken in birds' evolutionary history. Birds' tails got shorter, their flying skills got amend and their brains got bigger than those of dinosaurs. And mod birds, different their Maniraptoran ancestors, have a large toe that juts away from the other toes, which allows birds to perch. "Yous gradually become from the long arms and huge hands of non-avian Maniraptorans to something that looks like the chicken wing you go at KFC," says Sues. Given the extent of these avian adaptations, information technology'southward no wonder the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds as nosotros know them remained hidden until paleontologists started analyzing the rich fossil tape from Mainland china.

Chaoyang is a drab Chinese city with dusty streets; in its darker corners it's reminiscent of gritty 19th-century American coal-mining towns. But to fossil collectors, Chaoyang is a paradise, simply a 1-hr bulldoze from some of the Yixian Formation's most productive beds.

One street is lined with shops selling yuhuashi, or fish fossils. Framed fossils embedded in shale, often in mirror-prototype pairs, tin can exist had for a dollar or two. A pop item is a mosaic in which a few dozen pocket-sized slabs form a map of China; fossil fish appear to swim toward the capital, Beijing (and no map is complete without a fish representing Taiwan). Merchants sell fossilized insects, crustaceans and plants. Occasionally, despite laws that preclude trade in fossils of scientific value, less scrupulous dealers have been known to sell dinosaur fossils. The most of import specimens, Zhou says, "are non discovered past scientists at the city's fossil shops, but at the homes of the dealers or farmers who dug them."

In addition to Sinosauropteryx, several other revelatory specimens came to light through amateurs rather than at scientific excavations. The claiming for Zhou and his colleagues is to find hot specimens earlier they disappear into individual collections. Thus Zhou and his colleague Zhang Jiangyong, a specialist on ancient fish at IVPP, take come to Liaoning province to bank check out any fossils that dealers friendly to their cause accept gotten their hands on of late.

Near of the stock in the fossil shops comes from farmers who hack away at fossil beds when they aren't tending their fields. A tiny well-preserved fish specimen can yield its finder the equivalent of 25 cents, enough for a hot repast. A feathered dinosaur tin can earn several 1000 dollars, a year'southward income or more. Destructive as information technology is to the fossil beds, this paleo economy has helped rewrite prehistory.

Zhou picks up a slab and peers at it through his wire-rimmed spectacles. "Chairman, come here and look," Zhou says to Zhang (who earned his playful nickname equally chairman of IVPP's employees union). Zhang examines the specimen and adds it to a pile that will be hauled dorsum to Beijing for report—and, if they are lucky, reveal another hidden branch of the tree of life.

Richard Stone has written nearly a Stonehenge burying, a rare antelope and mysterious Tibetan towers for Smithsonian.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/dinosaurs-living-descendants-69657706/

Posted by: aguilaronoten.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animal Is Considered The Closest Ancestor To Dinosaurs"

Post a Comment